iPhone X used Samsung's OLED display

Apple and Samsung have a long history of partnership and rivalry. Here's why these two vastly different companies have worked together in the past, why they ran into conflict, and what this means for their future, and their customers.

Apple sparks a flaming friendship with Samsung

Samsung has been one of Apple's component suppliers for decades, initially supplying mostly hard drives and RAM for Macs in competition with many other companies. But that relationship grew much stronger when Apple grew beyond being just a boutique, relatively low volume PC maker.

That began with Apple's 2001 launch of iPod, a new lifestyle device centered around a freshly developed, super thin new 1.8 inch Toshiba hard drive that had previously lacked any obvious use case, and a commodity ARM processor package from PortalPlayer.

The original iPod

Apple's ability to source advanced components from various manufacturers--and then sell its iPods as a premium-priced product in a sea of cheaper alternatives that didn't work as well--radically shifted the design and production scale of those components. Previously, it was largely the collective PC industry that had been shaping most trends in component demand, and Apple played only a minimal role in that.

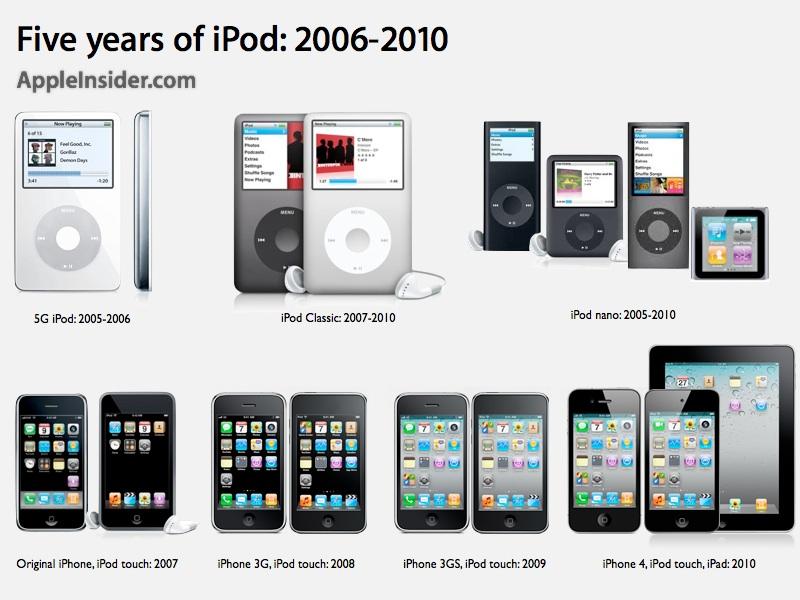

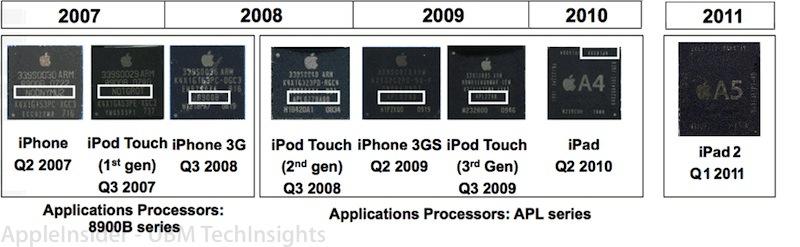

As the iPod took off and began selling into the tens of millions of units, it grabbed the attention of Samsung. In 2006 Samsung began providing Apple with an ARM processor that abruptly replaced PortalPlayer's in the original iPod nano. From that point on, Samsung began providing all of the ARM "System on Chip" brains for new iPods. It also began supplying Apple with flash storage chips for the 2G iPod nano and shuffle, along with a new 1.8 inch hard drive for Apple's 6G iPod Classic.

Apple sees the means of production

Apple's shift to flash storage in new iPod models was essential because the company had another device in the pipeline: iPhone. It couldn't use a hard drive for its storage. By introducing high capacity flash storage with iPod nano, Apple not only muscled into the flash MP3 market but also paid for the development of exclusive production lines of high-density storage chips in large volumes in advance of iPhone needing them. Building and operating a chip fab isn't just fantastically expensive; it requires special skills and knowledge. Apple couldn't just roll out its own chip factories to make enough parts for itself. It needed an established supplier.

At the same time, without a known customer lined up, it would be purely speculative and very risky for chip makers like Samsung to begin investing in the mass production of higher capacity chips. An idle chip fab rapidly loses money. But with Apple floating advanced offers to buy up the future production of such factories, Samsung and other makers could confidently shift away from what they were currently selling to develop faster and more advanced premium silicon they could sell more profitably in large, reliable volumes.

Steve Jobs showing off the original iPod in 2001

While Steve Jobs was the visionary showman marketing iPods to tech-hungry users, Tim Cook was his operations expert lining up the practical ability to build these devices in huge quantities with precise and scheduled pricing controls. The reason why Microsoft, Sony, Panasonic, and Samsung were all unable to effectively challenge Apple's iPods was partly because they had no Jobs, but also because they had no Cook.

Samsung discovers it needs Apple

While 1.8 inch hard drives had existed for a decade before iPod, Apple began buying them just as Toshiba reached a new level of sophistication that made them suitable for such a premium portable device. Toshiba's speculative development there had been lucky, not guaranteed. It occurred only after a decade of building the small drives that had not been easy to sell in any real volume. They were too small for a laptop and too expensive for any existing small device.

1.8 inch iPod drive

After iPod solidly established itself as a hit, Samsung jumped in to compete with Toshiba's supply of 1.8 inch hard drives. It then speculatively developed ever larger disks through the end of that decade. By 2007 however, Apple's interest in larger iPod classic capacity had peaked at 180GB, as its customers shifted toward its flash-based storage in iPod nanos, iPod touch, and iPhones. Samsung developed an even larger 250GB model, but Apple never used it.

Instead, Apple simplified its classic iPod offerings into a single, slimmer 120GB model. As the entire market for MP3 players faded and the demand for entry-level netbooks using 1.8-inch drives failed to materialize as expected, Samsung found itself without any high volume buyers for its most advanced 1.8-inch disk. After Apple discontinued last iPod classic in 2014, the entire 1.8 inch component category rapidly faded away into oblivion.

Samsung's ability to profit from component manufacturing involved more than just developing advanced technology and production capacity. It also required a buyer, ideally one with a big appetite for higher-end components. And nobody was buying up premium parts faster than Apple, because nobody was selling premium finished goods on the incredible scale of iPods. For everyone else, premium products were a narrow niche; mainstream volume sales demanded compromises to reach attractively low prices.

That was clear in the fate of PortalPlayer, which had been making most of its profits from sales to Apple. After losing Apple's business, PortalPlayer was sold to Nvidia, which then embarked upon selling its own chip platform for MP3 players and other mobile devices. But despite creating the Tegra chip platform that boasted of exceptional performance, Nvidia was unable to find itself a customer like Apple to buy its chips. It tried selling its silicon to Microsoft, Motorola, Google, LG, Sony, Acer, Asus, Lenovo--and even sold chips to Samsung, and tried to use Tegra in its own Shield hardware. Yet all of these products failed to sell in sustainable volumes that could keep Tegra profitable and maintain its advancement as a chip platform.

Without an Apple, Samsung could end up being another Nvidia Tegra.

Apple needed a Samsung

Apple couldn't mass produce and sell its premium products without a consistent and reliable, high-volume supply of state-of-the-art components. It painfully learned that over years of trying to coax sufficiently advanced PowerPC chips from IBM for its Macs. Apple shifted to Intel processors in 2006. But when it approached Intel to also produce chips for its upcoming new phone project, Intel declined.

Paul Otellini, Intel's chief executive at the time, later publicly revealed that he didn't believe his company would able to earn enough money building mobile chips for Apple's new iPhone to cover its development costs, largely because he couldn't imagine Apple being able to sell iPhones in large quantities.

Apple had also lost its confidence in PortalPlayer, so it turned to Samsung to produce its ARM SoCs for new iPods. That gave Samsung a vast new reliable customer for millions of its ARM chips, enabling it to confidently invest in ever greater SoC silicon sophistication. And that ensured Apple could source an advanced ARM SoC from Samsung for its far more sophisticated iPhone planned for release in 2007.

In parallel, Apple's modern solid state iPods began packing ever greater amounts of flash storage using premium, high-density chips. Samsung along with Hynix, Toshiba, and Micron developed the capacity to build enough flash storage to allow Apple to dramatically ramp up component production for its 8GB iPhones into the millions as demand turned out to be greater than expected. The economies of scale Apple realized also allowed it to lower its price, further broadening its appeal.

Two years after iPhone's introduction, Apple was buying out Samsung's entire production capacity, warping the global supply of flash storage in a way that made it hard for anyone else to build significant volumes for their own phones--or any other devices with similarly generous amounts of storage.

The myths of cheap value and expensive iPhones

Building a sufficient supply of components was critical because when the iPhone appeared, there were no existing smartphones with significant onboard storage or more than just the minimal RAM needed for running their baby applets. Listening to their customers, who were largely mobile operators seeking "carrier friendly, good enough" phones to give away to end users, phone makers were mostly building phones that could be sold as cheaply as possible. That necessitated minimal storage and RAM, and only "good enough" SoCs.

A recent idea, promoted by anti-Apple bloggers, that it was Apple that just invented today's $750-$999 premium tier smartphone pricing over the last couple years, is particularly puzzling because phones like the Sony Ericsson P990 and HTC TyTN were priced that high when iPhone launched. Yet they supplied only 64MB of RAM and mostly relied upon cheap yet slow SD cards for storage. Apple's original iPhone provided twice the RAM and built-in gigabytes of storage, at a much lower price because Apple was actually selling iPhones in huge volumes.

Many tech reporters and end users at the time clamored for phones with minimal built-in storage in lieu of removable SD cards, which could be upgraded cheaply down the line. However, removable storage complicated the physical and logical design of phones, limiting the size of apps and making it more difficult to manage apps and large documents like databases of photos, and made it effectively impossible to secure mobile devices and the data on them.

Apple's strategy of buying up high capacity storage chips in large volume orders and providing no means of expansion or removal prompted buyers to upgrade to more premium models that delivered a better experience. The original 4GB iPhone was discontinued almost immediately, enabling Apple to order even higher capacity chips. That, in turn, fueled the advancement of flash storage manufacturing. And that allowed Samsung to shift its production toward more advanced and profitable parts.

Outside of Apple, there was no high volume demand for advanced flash storage in everyone's pockets. Phone makers were desperately trying to build handsets for less than $150, which mobile operators could give away to their subscribers every two years as a subsidized device that locked them into a long term contract. That necessitated SD Card-based storage, which kept phones acting more like simple Nintendo video game consoles capable of only running rudimentary applets rather than being powerful general purpose computers with secure and reliable storage and sufficient RAM to support "desktop class" software.

Samsung turns on Apple with rival consumer devices

After years of seeing Apple's iPods sell profitably and witnessing the launch of iPhone as a star competitor that made its existing Omnia smartphone portfolio of Symbian and Windows Mobile phones look like old fashioned hot garbage, Samsung decided it needed to be better at developing markets for its own finished goods, rather than simply selling its best components to Apple. To do that, it would need something that looked a lot more like an iPhone.

After years of supplying Apple with parts, Samsung decided it could just be Apple

In 2009 it launched its first Android, the Samsung Galaxy, aka i5700, next to Apple's launch of iPhone 3GS. But notably, while Samsung was supplying parts for both models, its own flagship phone opted to use a far less powerful ARM chip, supplied only half the RAM, and provided only 8GB of storage, relying on problematic SD cards for expansion. Apple was already selling a 32GB iPhone. All of Samsung's choices dramatically lowered the production cost of the device, hedging against failure or limited sales.

At the same time, the Galaxy also debuted with Samsung's AMOLED screen. It also bested iPhone 3GS by supporting HSDPA "3.5G" mobile service, providing a higher resolution camera with flash, and a larger capacity battery. So while Samsung wasn't confident that it could sell the Galaxy phone in iPhone quantities that would support the higher cost of its fundamental components, Samsung was leveraging both its experience in building phones and its position in component manufacturing to give its own premium smartphone a competitive edge in other areas that it could demonstrate to buyers.

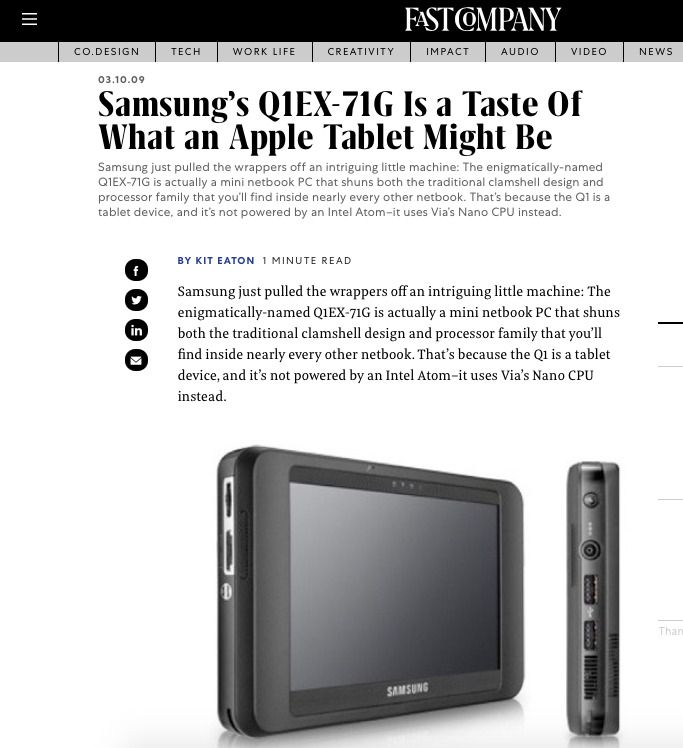

Samsung certainly wasn't competing with Apple for the first time. It was already selling MP3 players and commodity PCs, and had launched its Q1EX-71G tablet running Microsoft Windows, a new "ultra-mobile" device that was supposed to advance mobility beyond conventional notebooks like Apple's MacBooks, the same way that today's Galaxy Fold aspires to look novel and fresh, even if it's not expected to sell in quantity or be a practical product.

Samsung's $1300 UMPC showed off the industry's collective vision

None of Samsung's products felt finished or high quality, but they were also generally cheaper than Apple's offerings, appealing to the kind of "fast and cheap" buyer earlier described by Mr. Lizard. Samsung wasn't pulling away any significant number of iPhone owners; it was attracting a cheaper clientele, much the same way that Xiaomi and other "fast and cheap" brands began doing in China years later.

Apple invests more into its Samsung partnership

Around the same time, Apple was advancing from being a big buyer of mostly commodity components created by Samsung into a customized co-developer component partner. By 2008, Apple had determined that it needed to more actively control the design, production, and supply of its iPhone chips, in part to develop better processors than the market would speculatively create on its own. And it needed these chips not just for today's products but also in anticipation of its next ones, which included 2010's iPad and a new iOS-based Apple TV.

After three years of using custom Samsung SoCs, Apple launched its co-branded A4

Apple and Samsung collaborated on a fourth generation iPhone SoC design that Apple branded as A4. Samsung used the same chip internally under the branding Hummingbird, S5PC110, and later retroactively rebranded it as Exynos 3.

In 2010, Apple shipped the A4 as the powerful brain of its new iPad, followed by using it later that year in the all-new iPhone 4. Samsung used it in its second major Android flagship, the Galaxy S, which it also sold under Google branding as the Nexus S. Later that same year it used it in the Galaxy Tab.

Those moves provoked concern at Apple because it was now investing in a component supplier that was undercutting its own products. And more importantly, Samsung was now copying the design, marketing, and the software appearance and behaviors of its iPhone and iPad as closely as possible.

Apple and Samsung turn into frenemies

Apple was in a tight position because there was no other component producer available that could easily build its A4 chips, although rumors were already flying in 2011 that Apple was looking at Intel or TSMC. Apple's only real recourse was to sue Samsung over patent infringement, a move which would involve months of distraction and potentially interrupt a critical supply of not just its SoCs but RAM, storage, displays and other components Apple relied on Samsung to deliver.

While the original Galaxy had been more of a placeholder, Galaxy S gained some significant traction. Samsung claimed 10 million channel shipments of the new model in 2010. iPhone 3GS sold about 20 million units across its launch, but Samsung was picking up sales and mindshare. Galaxy S notoriety came in part because it was cobranded and promoted by Google, but also because it was broadly equated with Apple's iPhone because it looked virtually identical to Apple's iPhone 3GS.

Prior to Galaxy S, most Android makers had worked to develop original designs to steer clear of litigation with Apple. Now, all the philosophical excitement that Google was generating around Android as a platform was suddenly being packaged and sold by a major manufacturer going all-in on producing what appeared to be cheaper, virtually identical clones of Apple's work.

Samsung began closely following Apple's designs

This was also bitterly familiar territory for Apple, which in an earlier era had suffered through watching a close partner turn into a direct competitor, and then seeing that rival gain full legal rights to copy all of its technology and leverage it against the company. The history of Microsoft appropriating the Mac, and then winning Apple's "look and feel" lawsuits between 1988-1994 was also fresh enough for pundits to quote in predicting the same fate for iOS at the hands of Android, and largely Samsung.

This time, Apple appeared even more outmatched because it was fighting two close iPhone partners: Samsung and Google. And because Google was giving its infringements away, Apple could only really sue for financial damages against Samsung. And even if it won in court against Samsung, it would likely have to sue every other Android licensee to stop them as well. And back in 2010, there were still many Android licenses credibly posing as competitors to Apple.

By the end of 2010, Apple was sued by Motorola Mobility. It reciprocated with its own legal action, and shortly afterward sued Samsung in early 2011. Within a few months, virtually every phone maker was engaged in a tangle of lawsuits.

Apple and Samsung judged at Karmageddon

As their legal cases dragged on in courts around the globe, both Apple and Samsung suffered from the distraction. Apple eventually won far less than it hoped, and even that was reduced to be nearly meaningless. However, the case did expose the reality that Samsung had internally plotted to copy Apple as closely as possible, erasing the idea that both were just developing similar designs in parallel. That didn't go unnoticed by consumers.

The trials also revealed a variety of embarrassing facts, including the reality that Samsung's Galaxy Tab wasn't really selling beyond the bluster of the company releasing figures to bamboozle the press, citing "shipments" that were actually just barely enough to stock the global channel with inventory.

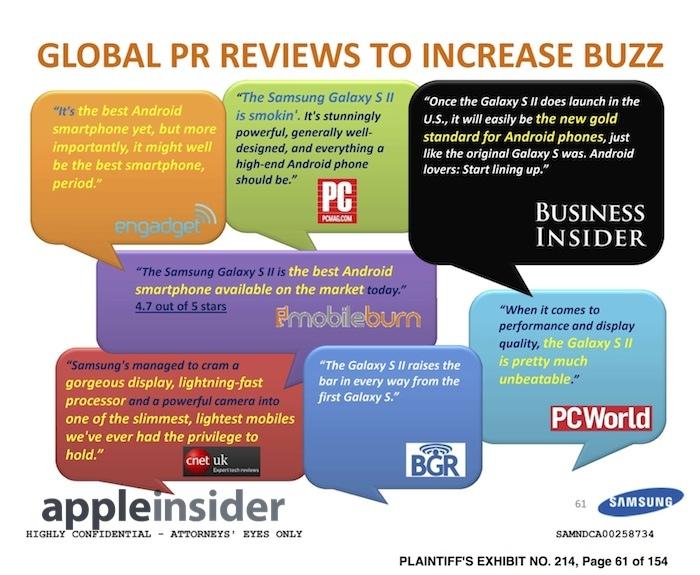

Trial exhibits of Samsung's "highly confidential" documents also revealed the company felt desperately outmatched by Apple, stating in 2011 that, "looking deeper into iPhone 4S, it is clear Apple is not worried about us as a hardware competitor," and detailed the component maker's "Global PR Reviews" initiative, where influential blogs were given special attention to facilitate glowing reviews that might get users talking about its products.

Samsung's hope that it could take advantage of its own component manufacturing to sell premium priced consumer products without Apple had driven it to copy not just iPhone and iPad, but also iPod touch with its Galaxy Player. It also introduced its own original product concept with the Galaxy Note phablet, and later launched new products before Apple, including its Gear smartwatch and Gear VR headgear. It partnered with Microsoft on new PCs and with Google on ChromeOS netbooks. Yet outside of phones, none of these other products were selling well or making any money.

In contrast, and despite the predictions of commodity pundits, Apple continued to sell leading numbers of premium iPhones, huge numbers of iPads, and went on to successfully launch Apple Watch and AirPods, emphasizing a vast gulf between the two companies' ability to consistently design and deliver product hits, to effectively build them in vast numbers, and then successfully sell them at a sustainable profit. Samsung couldn't, Apple could.

Once Samsung stopped "slavishly" copying iPhone, its high-end Galaxy S sales began to taper off. In early 2013, Samsung could boast that it had shipped 100 million Galaxy S units across three generations, compared to about 319 million iPhones Apple had sold to date, with each new Galaxy model significantly expanding upon the previous year's model. But after peaking with Galaxy S III, Samsung's high-end phone sales growth began to plateau and then contract.

In part, that was because Samsung wasn't as overtly copying from Apple or as effectively borrowing on its reputation. But it was also in part due to Apple copying something Samsung had worked for years to popularize: larger phones. The introduction of iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 Plus in 2014 had a dramatic impact on the sales of Samsung's larger phablets, which had been driving Samsung's phone unit profits.

If nothing else, Samsung's years of unrestrained, shameless copying of Apple's work had effectively given the iPhone maker a free license to take away what Samsung had been working on for years. Except in Apple's case, it was wildly successful in moving into and taking over Samsung's home territory of phablets.

Apple lives on without as much Samsung

The launch of larger iPhone 6 models in 2014 was particularly devastating for Samsung because those new iPhones switched from Samsung built SoCs to Apple's new A8 exclusively manufactured by rival chip fab TSMC. Additionally, Apple heavily promoted their new Retina HD screens, which were not built by Samsung and didn't use its OLED technology, giving the phones noticeably better color accuracy and wider viewing angles. Apple also began sourcing more of its RAM and flash elsewhere.

This one-two punch dramatically reduced the component income Samsung was getting from Apple's sales while also massively dampening the profits Samsung's entire Mobile IM division was earning from big phones, making it increasingly difficult for Samsung to invest in building advanced technology for its own phones, given the diminishing returns it could expect to recoup.

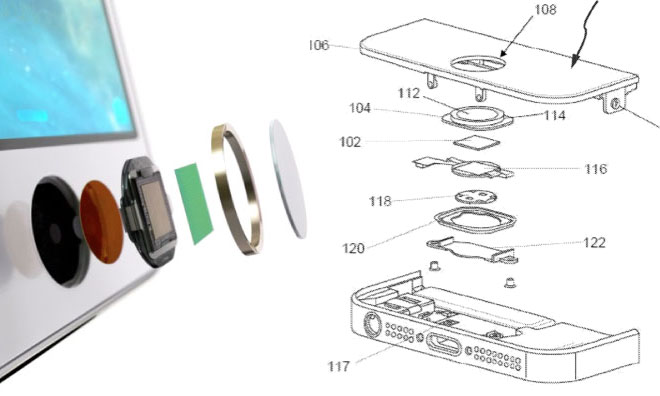

Additionally, the previous year Apple had introduced an entirely new technology that wasn't sourced from Samsung: Touch ID. Rather than collaborating with Samsung, Apple found and exclusively acquired the only supplier of advanced fingerprint sensors.

Apple didn't collaborate with Samsung to deliver Touch ID

Apple then sold tons of iPhone 5s models with it, immediately drawing significant attention to the fact that iPhones now had much better, effortless security that protected your data from casual snooping. It was even beginning to thwart a plague of smartphone thefts.

Samsung had to scramble to find a fingerprint alternative, and ended up with a clearly inferior version just before Apple began selling its larger iPhone 6 models that erased Samsung's exclusivity in big phones. Apple was now selling dramatically larger volumes of iPhones that were using far fewer Samsung components, while Samsung was struggling to find any sales growth in its own high-end phones.

While Samsung had introduced some attractive, exclusive features of its own, including water resistance and wireless charging, the next year its premium Galaxy S7 was still only selling about 55 million units--about the same as Galaxy S III had--while Apple was consistently selling around 200 million iPhones every year.

At the end of 2017, Apple's "all-premium" lineup of iPhones narrowly outsold Samsung's entire range of phones that sold for, on average, only about $250 each in the winter quarter. It did this again the following year, and appears to have repeated it this year, too.

Samsung's IM Mobile phone division had shifted from rapidly growing, profitable sales into an increasingly expensive effort that wasn't reliably paying off and certainly wasn't growing. Two years later, Galaxy S9 was down to shipping only around 30 million units.

Samsung seeks out Apple's business and finds an OLED win

Samsung won back production of part of Apple's A9 chips, but again lost out to TSMC with the A10 and all of Apple's successive SoCs. It's unlikely to win that business back. However, it did score an exclusive win in delivering Apple's first OLED smartphone screen for iPhone X.

Samsung's development of OLED technology provides an interesting view into how well the company performs as a component vendor compared to a finished goods maker to rival Apple. Samsung began shipping its first OLED Android phones ten years prior, but these early generations of OLED had terrible issues with color accuracy and viewing angles. They looked cheap, but they represented new technology and that appealed to some tech enthusiasts.

Samsung invested a decade of research and development into improving its OLED screens, with only minimal payout from its own, moderately profitable phones and from sales to other manufacturers of low priced Androids. Similar to Toshiba's mini hard drives, the big break for Samsung's OLED came with its partnership with Apple to drive a new product release.

By 2017, Samsung's own high-end phones were already using pretty impressive OLED panels, but that wasn't driving any sales growth. Over several years, Samsung had even made its flexible OLED screens a key marketing feature of "Edge" branded Galaxy phones by bending the touchscreen display to continue around the side of the device. This made for a fast-fashion distinction in styling, but the feature wasn't really practical, as it gave the device virtual buttons on the edge that were extremely easy to accidentally hit. Notably, Samsung no longer promotes its Edge display as a feature. It was a gimmick fad with limited commercial appeal, like the similarly discarded Iris scanner.

Apple, however, took Samsung's flexible display panels and created an entirely new look for iPhone X, bending the display back on itself to create uniquely rounded corners and a slim bezel margin that helped contribute toward massive sales of the distinctive product, even at a premium price.

Samsung supplied the high-end, flexible OLED panels used by iPhone X

Samsung was already offering some Galaxy models at similarly high prices, but it only managed to sell these in very limited numbers. Apple's ability to sell the $999 and up iPhone X to massive mainstream audiences was a win for both companies. But the decade long development and broad deployment of today's best OLED technology also required both companies, each following a different trajectory.

Without Samsung incrementally advancing what was originally a terrible looking display at low ball prices across an entire decade, Apple wouldn't have been able to source an advanced flexible OLED panel at a reasonable cost to use on modern iPhones.

Bloomberg's brand-fanning bamboozlement

The perfect symbiosis between Samsung's technically advanced components business and Apple's mastery of designing and selling consumer products often gets little attention. In part, that's because sensationalist bloggers like to deny reality and instead paint a picture where Samsung is actually an equally competent, innovating product designer and Apple is just a massive advertiser that fools the public with deceptive marketing to get them to pay too much for what is really just commodity gear.

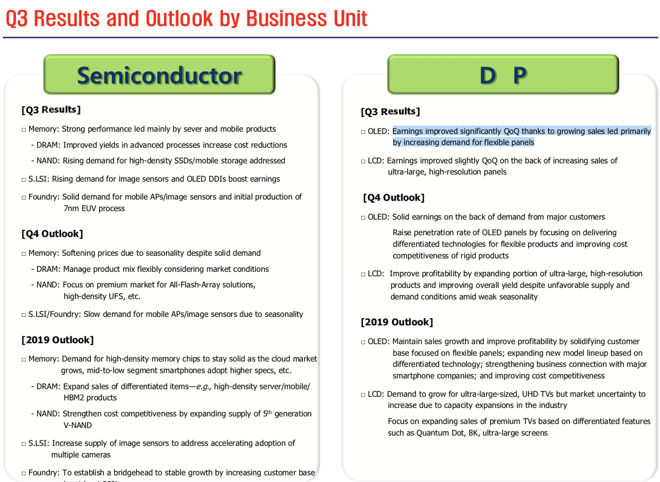

As iPhone X rose to success, all of the resources of Bloomberg were focused on how the new phone must be an embarrassing failure because Samsung's display panel division building OLED screens was reporting competitive pressures--with the assumption that this could only mean Apple's new phone was tanking.

Yet the clear reality was that Samsung was continuing to struggle to sell its own premium phones, and component sales of high-end flexible OLEDs to Apple were actually offsetting its Galaxy failure and keeping Samsung afloat. This was overtly outlined in the company's financial reports, which noted that "demand for flexible panels remains strong in the high-end segment," while also stating that "profitability in the mobile business is expected to decline quarter-over-quarter due to stagnant sales of flagship models amid weak demand and an increase in marketing expenses to address the situation."

Samsung reported that "demand for flexible panels remains strong in the high-end segment"

The truth was actually a far more compelling story than the tired tripe Bloomberg decided to rattle off instead. The only explanation is that its writer is simply a fan of cheap looking, "good enough" products and out of touch with the fact that most people with any discretionary spending clearly prefer the higher quality designs Apple sells for around the same price, leveraging the best components Samsung can produce, calibrated to Apple's highest standards.

Does anyone who is ready to pay $1,000 for a phone really expect that it is going to be loaded with as much adware crap as a $300 PC? Samsung's Galaxy S10 is. It can copy the iPhone X price tag, but can't copy its level of class.

It's pretty clear that Samsung is not anywhere near Apple's level in reaching customers with high-quality luxury-class gear. Otherwise, it would have been consistently successful across the last decade, rather than being most famous for a firey recall and an embarrassing prototype publicity stunt bookending a series of marginal failures. If Samsung didn't desperately need Apple, it would have successfully cut Apple loose long ago and just kept all the money in consumer electronics. It tried to do that and failed.

On the other hand, it's not Apple that's spending--and has spent--incredible tens of billions of dollars on global brand marketing, only to burn everything down and undercut its own reputation with flop watches, silly headgear that had to be recalled because it was built around a device with faulty batteries, and a long series of flashy but not very practical designs with the lifespan of some teenage fashion from H&M. Apple spends relatively little on advertising compared to its peers, and nothing compared to Samsung.

Frenemies forever?

One ongoing risk to Samsung is that there are lots of other component suppliers that also want Apple's business. Just as Samsung lost Apple's SoC fab business to TSMC, it is likely to also lose Apple's business to other OLED makers that are now approaching Samsung's capacity and ability. That competitive threat should keep Samsung on top of its game, knowing that while there are lots of potential Samsungs hoping to emerge out of China, there are not any other Apples out there both willing and able to source millions of its highest-end components.

At the same time, Samsung's efforts to compete with Apple in finished goods appears to have also improved Apple's performance. Without Samsung rushing out big phablets that too many people initially appeared garish and ridiculous, but found a niche, Apple might not have been so quick to develop its own larger iPhones. Without Samsung's clumsy Gear watches rushed out to market, it's possible that the Apple Watch team might not have worked as hard to set itself apart as sophisticated and elegant.

Samsung has fumbled through tablets, throwing out all kinds of ideas to see what might stick--experimenting with a stylus and trying sizes from tiny to huge. But that competitive pressure has also forced Apple to keep enhancing its products to stay ahead and appears to have pushed Apple to examine the potential for selling an iPad mini, larger iPad Pro models, and to match and surpass Samsung in designing its Apple Pencil for precise drawing.

In a world without Samsung, Apple might grow too complacent, deciding that it could just sit back and collect the same money while exerting a bit less effort. In the late 80s, Apple was clearly far ahead of commodity PC makers, and had little real competent competition. That didn't work out so well for Apple or its customers.

Today, Apple again doesn't really have much credible competition in personal computing. But rather than relaxing, it's fighting its way into new markets with wearable fashion, healthcare, home, audio, auto integration, and other new markets where credible competitors do exist.

Samsung's own Mobile IM division--the maker of Galaxy, Gear, Note, and Chromebooks--is effectively the closest thing to Apple out there, and it's still not very close. And while a world with no Samsung and just Apple is sort of frightening just by how much everything would cost, a world with no Apple and just Samsung would be almost as expensive but shoddy and sloppy.

Rather than trying to take out Apple, something it clearly lacks the capacity to do, Samsung should recognize the larger threat isn't its closest partner paving the road for high-quality premium consumer products. Instead, Samsung's biggest threats are the Samsungs of China, all struggling to cheapen the market and lower buyers' expectations so they can compete for unit sales.

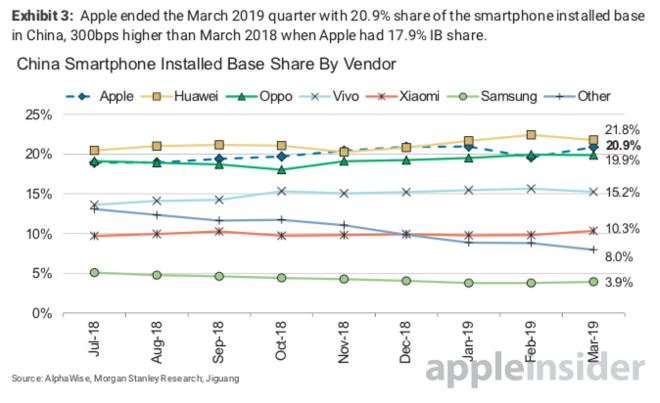

Huawei was supposed to be a threat to Apple, but it's really killing Samsung. Source: Morgan Stanley Research

Apple is helping keep Samsung afloat as the once leading brand in China loses both its finished goods and component sales to the same sort of desperate lower-end copycat cloners that Samsung represented back in 2011. So rather than taking potshots at Apple, Samsung should be racing to differentiate itself from Huawei, a company that is much closer in competence to Samsung than Samsung has ever been to Apple. And Huawei has already done far more damage to Samsung than Samsung ever managed to do to Apple.

Samsung's last twenty years of partnership with Apple have caused it to grow and flourish, despite the rough patches. In contrast, its last five years of contention with rising Chinese brands have been devastating to the Galaxy brand.

Maybe Samsung should keep its frenemies closer.

https://appleinsider.com/articles/19/04/23/editorial-super-frenemies---why-the-world-is-better-off-with-both-apple-and-samsung

2019-04-23 11:45:11Z

CAIiEGXBjw9gSe_1fstNYJYDa8IqFQgEKg0IACoGCAow9ckFMIBVMLCfBA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Editorial: Super Frenemies - why the world is better off with both Apple and Samsung - AppleInsider"

Post a Comment